| Don't like ads? | No ads |

*Bourbon Culture is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Table of Contents

- From Seagram’s Glory Years to MGPI’s Future

- Seagram’s purchase of the Lawrenceburg Distillery

- Four Roses and the Jos. E. Seagram Distillery- A Tale of Two Lawrenceburgs

- Four Roses Mashbills

- MGPI Mashbills

- Four Roses Yeast Strains

- MGPI Yeast Strains

- The Lawrenceburg Distillery under Pernod Ricard ownership

- CL Financial and the Financial Collapse of 2008

- LDI becomes MGPI

- MGPI expands outside of Lawrenceburg to obtain more storage facilities

- MGPI decides to bottle their own product

- The Future of MGPI

From Seagram’s Glory Years to MGPI’s Future

The growing bourbon and whiskey trend in the US is experiencing a renaissance much like the wine and craft beer explosions of the 90’s and 00’s.

Every distiller in Kentucky has been dumping millions of dollars into pristine landscaping, educational tours and new facilities to give each distillery its own unique appeal and lure to the tourists and whiskey enthusiasts alike.

Even the Tennessee distilleries have embraced the whiskey tourism.

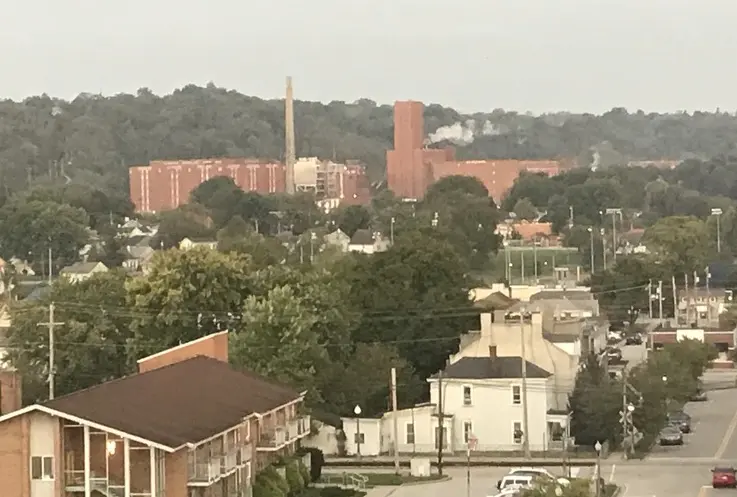

But in a small pocket of Indiana, nestled next to Kentucky and Ohio along the Ohio River stands a large brick campus with the words “Seagrams Since 1857” still spelled out in white bricks on the tops of the buildings that poke up across the hilly horizon.

This industrial-looking complex is home to the whiskey that is found in literally hundreds of different bottles nationwide. Yet there are no manicured grounds, no craft cocktail bar, no tours and no visitors allowed.

What is this place and why does it exist right here? Why not in Kentucky?

Early history behind the plant and distilling operations in this part of Indiana can be found in many different online articles.

But geography played the most important role in why this area was picked for distilling. Lawrenceburg, Indiana’s location right on the Ohio River provides easy and cheap transportation channels to move products up and down the Mississippi River to the East Coast, it also sets above a massive underground limestone shelf that spans across much of the state of Kentucky and provides the water necessary to make a great whiskey.

What’s up with that limestone-filtered water?

Basically it removes iron and sulphur (two things that will taint fermented products) and has a high calcium content that results in a higher pH.

That higher pH aids in fermentation. Great water leads to great whiskey and every distillery needs lots of it. But to truly understand the modern-day history of the distillery at Lawrenceburg, Indiana, you must first look back to 1933.

Seagram’s purchase of the Lawrenceburg Distillery

In 1933, a Canadian company named Seagram’s (owned by Samuel Bronfman) purchased the Lawrenceburg, Indiana distillery. Samuel’s (or Mr. Sam as he’d be remembered) first task was naming the plant the “Jos. E. Seagram Lawrenceburg Plant.”

The timing was perfect as America had just started to exit the Great Depression and Prohibition had come to an end. This meant that Americans would soon have much more money to spend on things like distilled spirits while also being legally allowed to buy them again.

Seagram’s began to invest large amounts of money into building up a modern-day distillery with enough capacity to satisfy the demands of not only a country coming out of Prohibition, but the world as well.

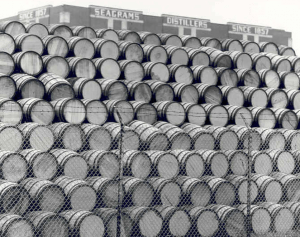

Quality control and efficiency were built into every step of the distilling process. After new distilling equipment was installed, the building of large warehouses to store and age whiskey was priority.

Seagram’s approach to aging their barrels of whiskey was different from the warehouses and rickhouses that stored bourbon for Kentucky distilleries.

Whereas a majority of Kentucky warehouses were built out of wood, the warehouses at the Lawrenceburg distillery were all brick structures with concrete floors separating each level.

This sturdy design was pursued due to its ability to age whiskey much more uniformly by discouraging heat collecting at the higher levels. Therefore each level of the warehouse would remain more or less the same temperature.

The Jos. E. Seagram Lawrenceburg Plant in Indiana began churning out various distillates including whiskey, clear spirits and other malted beverages for the Seagram’s portfolio right away.

But it was the whiskey that was the most alluring product to come off the stills. In the beginning, production was geared toward their two flagship whiskey products: Seagram’s 5 Crown and 7 Crown.

Both were a blended whiskey product, which meant that the whiskey inside was produced at more than one distillery and was made up of more than one mashbill before being blended together and bottled.

These whiskies by themselves would have been labeled as bourbon, rye whiskey, corn whiskey and Canadian whiskey by today’s standards because that is essentially what went into the typical batches of their products.

It was a very different product from the modern day Seagram’s 7, which now has a large percentage of Grain Neutral Spirits blended into it (nowadays believed to be 75% of the volume of a bottle).

The story of how 5 Crown and 7 Crown got their names is not because of how many different whiskey recipes went into the finished product, instead, they came about when Mr. Sam was presented with multiple varieties of blended whiskey to choose from.

He ended up selecting the 5th profile variety and the 7th profile variety as the ones that Seagram’s would produce. Thus, the names were born for each.

While enthusiasts today obsess over the specifications of their whiskey (mashbills, barrel entry proof, years aged, etc), many of these specifications were not hard and fast rules that were required to be duplicated with precision in the 1930s.

It was Seagram’s that seemed to lead the charge with their exacting standards and quality of whiskey that began to transform the industry all over North America.

It is believed that modern day MGPI bourbon and rye whiskey recipes have been around since the beginning of Seagram’s two iconic brands.

But you’ll never find these early whiskies bottled in single barrel or small batch forms due to the fact they were all distilled and aged for the purpose of being blended into 7 Crown and 5 Crown products.

Through much research, the exact year that these iconic whiskey mashbills were first developed is unknown, but we do know that as far back as 1966, when Jim Rutledge first began working for Seagram’s, that these recipes existed.

So although nobody from the 1930’s is still around to say for sure, it is a very real possibility that the same bourbon and rye whiskey recipes were invented in the 1930’s.

Seagram’s 5 Crown blended whiskey eventually disappeared from production as World War II demanded more industrial alcohols to be produced, but 7 Crown remained in production largely unchanged.

7 Crown was so popular world-wide that it was unofficially the first brand of whiskey to claim the world record of “1 million cases sold” followed later on by the first to sell 100 million cases (in the 1970s) and first to sell 300 million cases (1983).

So what exactly was the makeup of 7 Crown? Only Seagram’s knows which mashbills and which percentages of each recipe was blended into each batch, but in reality the batches were blended according to keeping a very consistent profile, so it’s likely that the exact percentages of each recipe fluctuated.

Pre-1990s 7 Crown is believed to be a blend of whiskey recipes that consisted of the 4 primary recipes that were made at the Lawrenceburg, Indiana Distillery (more on those recipes later on) as well as various Kentucky distilleries and Canadian distilleries.

In the 1960’s, Seagram’s began to tinker with production of a new kind of distillate called “Light Whiskey.” They were not the only ones though, as Schenley Industries, National Distillers, American Distilling and Publicker Industries also began to experiment with light whiskey as well.

It is not exactly known why the producers felt the need to develop a new category of whiskey, but production costs and the changing tastes of American drinkers (to lighter drinkers) were certainly at the forefront.

Light whiskey was created as a product that would bridge the gap between the ever-increasing popularity of vodka and more traditional “full bodied” whiskies.

Up until 1962, bourbon was still being distilled to around 107 to 110 proof, which made long aging times less necessary because the additional water content was much faster at extracting the sugars from the oak of the barrel.

This made bourbon much fuller and richer than the younger bourbons that are found on the market today. But in 1962, the government was persuaded by the industry to allow a new set of guidelines for distilling bourbon to bring up the maximum distillation proof to 160 and the maximum barrel entry proof to be 125.

Light Whiskey, on the other hand, was a product that was distilled between 160 to 189.9 proof. Light Whiskey also didn’t have a set mashbill or barrel entry proof, but Seagram’s elected to barrel theirs at 140 proof.

The mashbill that was used for Light Whiskey is known to be 99% corn and 1% malted barley (Fun Fact #1: The Light Whiskey recipe is known internally as “LJSS”).

The 1% barley is typically viewed as a necessity to aid the enzymes during the mashing process, but another reason it was designed this way was because European laws that stated that all whiskey must contain a percentage of malted grain in order to be called a whiskey.

So Seagram’s way around this was to include the smallest amount of malted barley necessary to keep this designation. The high proof that Light Whiskey was being distilled at stripped away much of the body and character and left behind a very light tasting spirit.

After distillation, Seagram’s aged it in previously used barrels for as long as was necessary.

At some point in the early 70’s, Seagram’s along with the other distillers, approached the TTB about officially creating the category of Light Whiskey along with its production standards and received an approval for it.

Seagram’s also produced a large amount of light whiskey at its Canadian distilleries with the Valleyfield Distillery in Quebec still producing large amounts of it for Diageo today.

Nowadays, Light Whiskey produced in Indiana that isn’t used in blended whiskies can be found bottled in products such as High West’s 14 Year Old Light Whiskey, Obtanium’s Single Barrel Light Whiskey releases, Joseph Magnus’s Murray Hill Club batches and even Backbone Bourbon Company’s Triple Down Light Whiskey.

Light Whiskey should not be confused with Grain Neutral Spirits (GNS), which is another product that the Lawrenceburg Distillery makes a lot of.

GNS are primarily used for blending or to make vodka and gins (Fun Fact #2: MGPI is the largest distiller of gin on the continent).

The difference between GNS and Light Whiskey is that Light Whiskey has a lower proof coming off the still (as was already mentioned, it can’t be more than 189.9 proof). But GNS must come off the still above 190 proof.

GNS usually utilizes the cheapest grain available on the market (which is almost always corn).

Since Seagram’s has never marketed their GNS as a type of whiskey, the makeup of a typical batch of GNS would forgo any malted grain and instead use 100% corn.

But not all GNS produced at the Lawrenceburg plant is 100% corn. Due to their strict quality requirements, any distillate that is considered low-quality or off-profile is ran through the still again to create a GNS out of it.

GNS were increasingly popular to blend into other whiskies because of the before-mentioned change in taste of the average consumer starting in the 1960’s and 1970’s that demanded a lighter spirit and taste.

With the technological advances of the 20th century being realized at everything from automobile manufacturing to computers, Seagram’s found itself with the opportunity to lean out their production by becoming fully automated in 1998.

It has been said that ever since automation took place, that the entire distillery could be ran by as few as 6 people if it ever came down to it.

But even with the cost savings being realized, Seagram’s as a beverage producer was on uneasy legs as a company. Edgar Bronfman Jr. (who was at the helm of the company in the 1990’s) sunk more and more money into the entertainment industry companies that he owned.

While the exact reasons for Seagram’s beverage empire dissolving are numerous and complex, the sale of the company was relatively straightforward.

The Federal government wanted the company’s assets split instead of being sold to one beverage producer to avoid creating a monopoly.

In 2000, newly formed beverage conglomerate Diageo and French spirits company Pernod Ricard finalized agreements to divvy up the assets of the former spirits giant.

Pernod Ricard purchased the distilling plant in Indiana and promptly changed the name to Lawrenceburg Distillers Indiana (LDI).

With this change of ownership came the official splitting of the close ties that bonded the Indiana distillery with the conglomerate of other North American distilleries to include the Four Roses Distillery, which had also been owned by Seagram’s up until this point.

Four Roses and the Jos. E. Seagram Distillery- A Tale of Two Lawrenceburgs

Before jumping into the history of the Pernod Ricard ownership era, it is important to look at the link between Seagram’s ownership of both the Four Roses plant in Lawrenceburg, Kentucky and the Seagram’s plant at Lawrenceburg, Indiana.

It should also be noted that Seagram’s owned other Kentucky distilleries, but would eventually shutter many of them due to the decrease in whiskey sales across the years.

The association between Four Roses and Jos. E. Seagram Distillery is one of the more fascinating pieces of history in modern-day bourbon lore.

In a podcast from a couple years ago, Jim Rutledge, the former master distiller of Four Roses, elaborated on the fact that quality control teams between both Seagram’s and Four Roses would test each other’s yeast strains to verify that no genetic drift was occurring.

In the same podcast, he also elaborated on the fact that the “V” yeast strain (internally known as Strain 133) is shared between Four Roses and MGPI to this day.

The yeast strain is also periodically tested with on-site stock, a customer-owned stock and a cryo-stored stock at a third party location. But there are many more similarities that continue to connect these two distilleries to this day.

Peeling back the curtain reveals that the Four Roses and the Lawrenceburg, Indiana Distillery still utilize the same recipe abbreviations that were invented during the Seagram’s era.

For example: a recipe that would be called OESV at Four Roses would actually be called LESV if it was distilled at the Indiana distillery.

The “L” is the designation that Seagram’s used to denote the Lawrenceburg, Indiana facility while the “O” designation was assigned to the Lawrenceburg, Kentucky facility for Four Roses

Many MGPI employees still joke to this day that the “O” in front of Four Roses recipes actually stands for “Other Lawrenceburg.” (Fun Fact #3: the “G” designation was used to annotate the Gimli Distillery in Canada, current producers of Crown Royal products).

The next letter indicates the mashbill that was used. Four Roses rounds down their low and high rye bourbon mashbill to 20% rye for “E” mashbills and 35% for “B” mashbills whereas MGPI’s ryed bourbon mashbills are often quoted as 21% for “E” mashbills and 36% for the “B.”

The truth is that these can fluctuate slightly with the amount of malted barley used (somewhere between 4% and 5% depending on beer density shifts).

So technically, MGP and Four Roses still use the same mashbills as each other. The third letter “S” is believed to stand for “Straight Whiskey” but in reality stands for “distilled Spirit.” The fourth letter stands for the strain of yeast that was used.

The Indiana distillery has access to use basically all of the yeast strains that Four Roses does (O, F, K, Q and V) as well (Fun Fact #4: The V yeast strain could not survive long enough to propagate in the Gimli, Ontario plant, so Seagram’s had them use a different one).

Let’s take a look at their similarities and differences in a broad scope:

Four Roses Mashbills:

- E – Low Rye: 75% corn, 20% rye, 5% malted barley

- B – High Rye: 60% corn, 35% rye, 5% malted barley

MGPI Mashbills:

- E – Low Rye: 75% corn, 21% rye, 4% malted barley

- B – High Rye: 60% corn, 36% rye, 4% malted barley

- Q – Rye Whiskey: 95% rye, 5% malted barley

- C – Corn Whiskey: 80% corn, 15% rye, 5% malted barley

- D – High Corn Bourbon: 99% corn, 1% malted barley

- Rye whiskey: 51% rye, 49% malted barley

- Rye whiskey: 51% rye, 45% corn, 4% malted barley

- Wheat Whiskey: 95% wheat, 5% malted barley

- Malt Whiskey: 100% barley malt

- Alt. Bourbon: 51% corn, 45% wheat, 4% malted barley

- Alt. Bourbon 51% corn, 49% malted barley

Four Roses Yeast Strains

- F

- K

- O

- Q

- V

MGPI Yeast Strains

- V (Strain 133)

- Q (Strain 74)

- O (Strain 202)

- K (Strain 103)

- S (Strain 1Y, primarily used in Light Whiskey production)

With all of this talk of rye, it is important to note that the most commonly used rye for whiskey products made at the Lawrenceburg, Indiana Distillery come from Germany while Polish, Swedish and Canadian rye are also used if it matches the profile that they’re looking for.

It should come as no surprise to learn that Four Roses also sources their rye primarily from Germany as well. One can assume it may be coming from the same producers.

So why Germany? The scientists at Seagram’s were always testing and tinkering to produce the best tasting spirits that they could make and tailor them to the locations that would distill them the best.

It was determined through much testing that a specific type of rye grown in Germany was producing the best mash for their yeast that would eventually lead to the best tasting distillate.

Germany is a top producer of rye and their grain breeding programs are developed by local farmers and university researchers whereby they track key statistics like ferulic acid levels which is a huge help for any alcohol producer.

By analyzing these levels, it helps to zero in on specific ferulic acid and arabinoxylan percentages that will give them the best efficiency for their production.

These Northern European ryes are prized for the flavor and size of the berries and low presence of chaff and other foreign material due to meticulous cleaning.

North American rye grain on the other hand tends to be dirtier and much more variable in their key components. But ever since the switch to European sources was established, the consistency of the congener profile has allowed the rye whiskey coming out of Lawrenceburg to remain world class.

The scientists at Seagram’s also implemented other practices across their brands that achieved more consistent and flavorful profiles such as using barrel entry proof of 120 for their whiskey (which both Four Roses and MGPI still utilize to this day) and building their warehouses either as single-story units or with the attributes of a single story unit, like the multi-story concrete floored warehouses at Lawrenceburg, IN.

The Lawrenceburg Distillery under Pernod Ricard ownership

With Seagram’s exiting the market altogether, assets of multiple distilleries were split between Pernod Ricard and Diageo to avoid monopoly laws.

A very strange relationship ensued whereby Diageo now owned a large majority of the brands that Seagram’s once made, but Pernod Ricard now owned a major facility that produced the spirits that were used for those labels.

Pernod Ricard now regarded their new facility in Indiana as more of a distillery that would be used to contract-distill for other brands than to actually make their own unique products at.

Diageo’s long-term contract with Pernod Ricard to make these spirits kept the distillery in the black while also having the capacity to seek other brands to produce for.

Thus began the business model that continues to this day with MGPI; contract distilling and sourced whiskey sales as the main focus of the plant.

The year was 2001 and the bourbon and rye whiskey boom still had not occurred. With a giant plant capacity, Pernod Ricard began to explore the market for all of the product they had in their warehouses.

Companies started to trickle in as America and the world were slowly changing their preferences to more unique and complex tastes thanks to a robust food and cocktail culture that was ignited by various internet platforms.

During this timeframe when the American sourced-whiskey industry was in its infancy, rules weren’t clearly established and improper labeling was commonplace among smaller bottlers.

Thus began a series of incidents where the public began to witness hometown brands sprouting up with their “own” whiskey for sale that was usually made in Indiana.

The most publicized incident occurred under Pernod Ricard’s ownership as they began to sell rye whiskey to the Templeton Rye Whiskey brand based out of Templeton, Iowa.

In 2006, Templeton Rye began to sell a rye whiskey with the words “Small Batch” and “Prohibition Era Recipe” on the front of their bottle. In no time at all, it was selling like hotcakes all across the Midwest.

Most consumers believed that this product was distilled in Iowa. However, it was not until many years later that it was discovered that Templeton Rye was actually distilled in Indiana.

Not only was the labeling incorrect, it was deemed to be outright false. A lawsuit settled the amount of money that Templeton had to pay back to consumers due to their labeling lapse.

To add insult to injury, the lawsuit also revealed to whiskey enthusiasts that Templeton took the rye whiskey and added an “alcohol flavoring formulation” made by Clarendon Flavor Engineers of Louisville, KY to achieve a specific flavor.

This brought to light a fact that rye whiskey that was not labeled as “straight” was allowed to have a certain percentage of flavor or color enhancers added in, cheapening the allure of how whiskey traditionally got its taste.

This would not end up being the last time that a product from Lawrenceburg Distillery ended up being incorrectly labeled as companies like Widow Jane and Whistlepig also failed to state on their labels that their bourbon and rye whiskey came from Lawrenceburg, Indiana.

Nowadays, whiskey enthusiasts are much more savvy to the methods of reading labels and determining sources.

Thanks to large online communities, there is not much that escapes their attention as they frequently call out companies to the TTB that are improperly labeling their products.

Currently, MGPI won’t confirm or deny if they actively encourage the companies that source their whiskey to label it correctly, but are adamant that all labeling for their own products will always be correct.

After Pernod Ricard’s purchase of LDI, the bond with Four Roses may have been broken, but they soon found themselves collaborating with the other distillery in Lawrenceburg, Kentucky: Wild Turkey (Pernod Ricard had purchased WT in the 1980s).

Pernod Ricard may have been especially motivated to purchase the Lawrenceburg, Indiana facility during this time because Wild Turkey had experienced a fire in 2000 that destroyed Warehouse J which contained the entire bottling operation for Wild Turkey products.

But with the large capacity of the bottling plant on site at the Indiana facility, Pernod Ricard switched bottling operations there until 2006 when they switched operations to Arkansas.

Another LDI-Wild Turkey collaboration during this time saw engineers and managers at LDI involved in designing the upgrades for a new barrel dumping line and dry house facilities for the Russell’s.

Several of these improvement drawings remain in the archives at the Lawrenceburg, Indiana plant to this day.

By 2006, Pernod Ricard had paid for an independent study to be conducted across its brands to determine which operations they could trim the fat from.

When the Lawrenceburg Distillery was examined, it was determined that the stills had more capacity to produce spirits than they were currently selling to their customers and that their warehouses were running out of room to put all of the aging stock.

This prompted Pernod Ricard to begin looking for a buyer for the LDI facility. CL Financial Group (also affiliated with Angostura Limited) reached an agreement with them and bought the LDI plant and the Charles Medley Distillery in Owensboro, KY towards the end of 2007.

CL Financial and the Financial Collapse of 2008

No ownership change is complete without a headache or two. As Pernod Ricard began to transfer management personnel out of Indiana, they also gutted a fair amount of documentation and Standard Operating Procedures.

Regardless of this setback, the most important pieces to the distilling operations at LDI remained behind in the form of personnel in critical positions.

Larry Ebersold, the Master Distiller for LDI, did depart with the company during this transition (and later went on to advise New Riff on how to run their distillery), but he left behind a fully trained mentor in the form of Greg Metze. Metze still retained core team members like Tim Dyer, John Netzley, Randy Graves, Pam Soule and numerous operators that stuck through the change of leadership to keep production numbers and the know-how up to par.

Fortunately during this time, the recipes, facilities and yeast remained the same.

There seems to be a widely held rumor that the distillate has changed from what was being produced during the LDI days compared to what is being produced today under MGPI ownership.

After much research into this theory, there seems to be no change in the distillation process, grain sources, mashbills or aging techniques.

One of the best explanations looks at the age of the whiskey that was distilled during the timeframe of Pernod Ricard ownership compared to the younger whiskey that has been distilled under MGPI.

It is a widely held belief among whiskey enthusiasts and Lawrenceburg, Indiana distillery workers that their whiskey has a sweet spot between 10 years old and 14 years old.

Simply put, whiskey distilled during LDI’s ownership period is perceived as better because it’s older. Distillate made during MGPI’s ownership still has not come of age yet, so it’s not going to be good as the well-aged products that have already been produced.

The other reason has to do with variances in the warehouses. This may not make a lot of sense because of the steps that Seagram’s took back in the day to have warehouses that would age consistently throughout the floors.

But there are several smaller details that create variances between every barrel of whiskey that rolls out. First of all, although many pictures of the warehouses at Lawrenceburg, Indiana facility show barrels being stored on their side (aka, in ricks), the large majority are actually stored on palates (upright).

Though not as sexy as barrels stored in a rickhouse, palletizing barrels makes more sense in term of volume able to be stored.

There are also slight differences in a barrel stored upright versus a barrel stored on its side. Additionally, some warehouses that were closer to Tanner’s Creek (a local creek that flows along the west side of the campus) create additional climate variances inside the warehouses through higher humidity in the summer.

These higher humidity levels would actually increase the amount of alcohol evaporation within the barrels, resulting in the distinct pattern of low-proof whiskey coming from the distillery.

Some Indiana-bourbon lovers who swoon about older barrel proof bourbons with low ABV numbers would probably find out that their barrels came from the warehouses (and sides of the warehouses) that were especially close to Tanner’s Creek.

Unfortunately, very little information is usually given by companies that source single barrels from MGP as to which warehouses and which levels the barrels came from.

With CL Financial (CLF) in control of the plant, it was a gamble on if they would be able to move the large stores of whiskey that now filled their warehouses.

That unknown was soon answered with a resounding thud of the worldwide recession that hit in 2008. With many Americans out of jobs or with no discretionary income, alcohol producers joined many other industries in a freefall.

By time the bleeding had stopped and the economy began to heal, CL Financial was ruined. LDI was listed for sale again, looking for its 4th owner in just over a decade.

The plant was finally sold for a paltry $29 million (which roughly equaled the value of all of the aging product on site) to MGP Ingredients in late 2011.

LDI becomes MGPI

MGPI was a giant conglomeration of food producers in the United States at the time of the Lawrenceburg Distillery acquisition.

MGP already had a large distilling operation in Atchison, Kansas, but looked favorably upon its acquisition of an aged whiskey producing powerhouse.

The timing for this acquisition couldn’t have been more perfect as another key trend in 2011 and 2012 saw alcohol and distilling laws across the USA begin to ease following the boom of the craft brewing industry.

Craft distilleries were now obtaining legal status to open across the US. But the difference between breweries and distilleries is that while a brewery could have products out in months, distilleries needed years.

This led to a wave of distilleries looking far and wide for large stocks of aged whiskey to supplement their operations before their own whiskey could be aged and released. MGPI swung open their doors and the barrels began to roll out.

But by 2014-2015, it began to appear that perhaps MGP had let too many barrels roll out too quickly. NDPs like Smooth Ambler, Mayor Pingree, Traverse City and others had purchased large amounts of MGP barrels only to return to MGP as they began to run out and were informed that there were no more left.

A large majority of the stock that remained were purchased through contract agreements with other smaller NDPs until no more unclaimed barrels remained in the warehouses.

This has led to an interesting spattering of small craft distilleries around the US offering limited amounts of highly-aged MGP bourbon and rye whiskey for a year or two before running out completely.

Companies like Traverse City, Blaum Bros, Litchfield, Bull Run, Chattanooga 1816, Boone County and Manifest all built early reputations on the backs of MGP barrels before running out and releasing their own products to their fan base.

Some whiskey companies retain long term contracts that see their output reduced, but steady in terms of aged whiskey from MGP.

These companies typically have one thing in common; they have a large umbrella corporation that they’re under that increases their buying power.

Constellation’s High West and Belle Meade brands continue to have access to moderately aged rye whiskey and bourbon while Diageo-owned Cascade Hollow (George Dickel) and Bulleit Frontier Whiskey also use their buying power to keep the rye whiskey flowing.

MGPI expands outside of Lawrenceburg to obtain more storage facilities

In MGPI’s current assortment of warehouses, there exists a unique, single-story, metal-clad building with a concrete floor that is used primarily for experimentation.

The workers at MGPI commonly refer to this building as “Iron Clad.” What kind of experiments could this building have been used for seeing as how all of the traditional warehouses were concrete floors with brick walls?

An assumption is that the effects of barrel aging in regards to the highly conductive metal walls were studied (ala Warehouse H at Buffalo Trace).

Another assumption is that scientists and master distillers would conduct comparisons of their distillate aged in the conventional brick and concrete warehouses to those that were aged in a warehouse with metal walls to strategize about future warehouse designs.

It may never be known if the data influenced the management at MGPI to lean in one direction or another. But teams were dispatched in the early 2010’s to begin the search for suitable facilities to expand the limited storage space at the Lawrenceburg facility.

The Lawrenceburg, Indiana facility is somewhat landlocked in the fact that the town grew around it, leaving no space for new warehouses to be built near their campus.

However, with contract distilling for new whiskey customers reaching new highs, it was imperative that MGPI expand their facilities.

The race was on to find facilities that fit the general profile of the kind of structures that MGP was already using.

They may have also been instructed to include warehouses with metal walls on their list as well. Looking across state lines, MGPI found a recently-closed pipe manufacturing building in Williamstown, Kentucky that could be easily converted into a barrel-aging facility.

From the outside, it’s easy to see that one of the buildings has a concrete floor and (painted) brick/block walls. The other warehouse appears to be metal clad.

Those two buildings are able to store 45,000 and 65,000 barrels respectively. Next, the expansion team looked within their home state and found a massive warehouse in Sunman, Indiana that was previously owned by international packaging company Deufol.

This warehouse can store a massive amount of barrels, to the tune of 300,000, which may make it one of the largest barrel-aging warehouses in the world.

A secondary building (believed to be metal clad) in Sunman was also purchased, creating a huge amount of space that will surely keep the USA afloat in MGP products for decades to come.

Will these metal clad warehouses eventually produce whiskey that strays away from the typical MGP profile? Time will tell but it can be speculated that in an effort to encourage faster barrel aging to customers who want products that taste older, that these new metal-clad buildings probably could be used to speed up the aging process while also trying to keep the traditional aging methods alive.

This is not an unexpected move at a time where the industry still sees shortages and high prices for aged products. But with two satellite storage locations around 20-40 miles away from the main campus at MGPI, how will this different geography affect the final product?

Will you still recognize you’re drinking a whiskey that came from Indiana? Additionally, will whiskey that is distilled in Indiana but aged in Kentucky be able to have the designation “Straight Whiskey” on a future label?

MGPI decides to bottle their own product

For almost 7 decades, workers at the Lawrenceburg, Indiana facility could go to their local liquor store and find a bottle sold by the same company that they worked for: Seagram’s.

But all that changed in 2001 when Pernod-Ricard took over. The distillery’s new business model was now to make whiskey (and other spirits) that would be sold to other companies for them to bottle under their own label.

In fact, the downfall of Pernod Ricard’s time of ownership over LDI is speculated to have been because they had so much capacity but not enough people to sell it to. The CL Financial ownership period experienced this as well.

MGPI decided that they would begin to control their own destiny by creating their own brands to sell on their own.

In 2014, 3 years after MGP first took over the operations of the Lawrenceburg plant, they bottled a limited release of their own bourbon for the first ever Lawrenceburg Whiskey City Festival.

Named “Metze’s Medley Indiana Straight Bourbon Whiskey,” under 1000 bottles of 80 proof bourbon were blended by master distiller Greg Metze and were sold off with all proceeds going to the United Way.

Little did most consumers realize that this may have actually been a test to see how the public would respond to a product that was made, bottled and sold entirely by the company that produced it.

In 2015, Greg Metze was given the green light to blend up the first bottling of bourbon that MGPI would distill, age and bottle on their own grounds since Seagram’s last owned the company.

Metze’s Select was a limited release (6,000 bottles) of 3 different bourbons of various ages and mashbills that was bottled at a rather mild 93 proof.

The reception to this release was so positive that it spawned the release of 5 new whiskey products over the next 3 years. Remus Repeal Reserve, George Remus (both bourbon and rye whiskey) Rossville Rye Whiskey, Eight and Sand Blended Bourbon Whiskey, Tanner’s Creek Bourbon.

As recently as 2020, MGPI took yet another step forward by recognizing the whiskey enthusiast’s thirst for single barrel products. For the first time ever, MGPI would now have their bourbon bottled from barrels that the customers would hand-pick.

The Future of MGPI

The headlines from January 2020 were awash with the news that MGP’s stock had plummeted 24% after a report came out of the shortfall in the sales department of whiskey to customers.

For the super-fans of MGP, this was head scratching news. Common complaints seem to stem from whiskey fans saying that MGPI prices their barrels out of reach or that they have to buy millions of dollars of products before they have access to the best aged barrels.

I believe that this is not the case anymore. Simply put, every barrel that’s over 6 years old has been spoken for inside of their warehouses.

Those customers are either using them right now in their products (look at how Belle Meade continues to put out a limited amount of 7-12 year old bourbon for the last 4+ years) or new ones are popping up with a large stock of it, selling it off at a fast rate (Smoke Wagon is a good example of this, releasing bottles towards the end of 2018 to the current day).

MGP whiskies were so sought after that any product aged for more than 10 years was guaranteed to sell out instantly and fetch huge premiums on the secondary marketplaces.

Many young distilleries announced in that timeframe that they had ran out of their MGP barrels and would now be selling their own since they couldn’t get any more, a statement that baffled enthusiasts.

Small batches of 10+ year aged bourbon and rye still pop up from time to time, but the truth of the matter was that every 10+ year old MGP bourbon that is released today has already been purchased years ago.

The customer was just finally coming around to collect their barrels and bottle them up. For everyone else, they had to settle for the young distillate that MGP had only recently started to produce.

It is common now to find many brands out there like Tumblin’ Dice, Smooth Ambler, Barrell Craft Spirits and Backbone Bourbon Company releasing 4-5 year old aged distillate simply because there are no older stock available for purchase.

It’s hard to put a number on just how many modern-day whiskey drinkers fell in love with bourbon or rye whiskey because of a product that the Lawrenceburg Distillery had produced.

But the simple fact remains that many brands built their fanbase on MGPI products and many more have struggled with releasing their own products that aren’t up to the level their customers experienced with MGPI products.

There stands a good chance that a number of those brands will have to re-convert to an all-MGPI portfolio of whiskey or at least run two brands simultaneously (much like how Nelson’s Green Brier produces their own whiskey, but will continue bottling their Belle Meade line of MGPI bourbon).

In the meantime, MGPI will likely continue to expand its distribution of their own brand until all 50 states sell their products (and then proceed to examine markets overseas).

It also seems likely that the 5 whiskey brands they currently bottle in-house will expand as their wheated bourbon comes of age (it’s currently around 7 years old now). This could very well turn into a potent Pappy alternative.

They also have a wheat whiskey mashbill that has already been bottled by a few NDPs (such as Backbone Bourbon) and instantly showcased its captivating potential despite still being young.

MGPI is still finding what it takes to make everything work after seeing two decades of internal change and external change within an industry that has seen unparalleled growth over the past 10 years.

There may be struggles and hiccups still on the horizon for the Lawrenceburg plant, but as long as the processes stay the same, some of the best whiskey in the US should continue to flow from the barrels produced there.

Great whiskey can never be rushed, but thankfully with the expansions taking place today, many bottles will be guaranteed to wear a “Produced in Lawrenceburg, IN” on their label long into the future.

Featured Products

- Neat Traveler

- View Larger

- Description:The Aged & Ore Neat Traveler is a complete travel kit for spirits. We combined our widely praised Neat Glass with one of our 3oz Flight Bottles and housed them together in a custom EVA travel case. Perfect for a night away with your favorite pour. The tie

- Bottle Flight

- View Larger

- Description:The Aged & Ore Bottle Flight is a premium set of 4 custom silicone wrapped glass bottles designed to transport and share samples of your favorite spirits. The flight bottles come in a custom EVA travel case that fits perfectly in any small bag. An Aged &

- Travel Bundle

- View Larger

- Description:This Bundle combines two of our crowd favorite products, creating the ultimate travel bundle to bring along your favorite spirits and glassware. Bundle Includes: Neat Traveler (Gray) Bottle Flight (Gray) Note: This bundle is only available in gray and col

*Bourbon Culture is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission.