| Don't like ads? | No ads |

*Bourbon Culture is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Introduction

Out of all of the distilled spirits for sale in the world, it’s whiskey that evokes such a strong romanticism among its enthusiasts. Think about it. When’s the last time somebody held their glass of vodka up to a light to admire its color or its aroma? I can’t say I’ve ever seen that happen.

The most obvious reason that people love their whiskey is because they love the natural beauty of how a spirit ages in a wooden cask – slowly becoming more complex and refined as the years go on. Sure, there are other spirits that are also aged in barrels like whiskey, but they’re typically aged in more tropical or hot climates (I’m looking at you, tequila and rum) for nowhere near the average lifespan as a barrel of whiskey. A majority of rum and tequila producers also love to load their spirits up with additives and flavorings to make their product more palatable to make a buck. Thankfully, most of the whiskey out there doesn’t allow that – especially bourbon.

Part of the allure of a bourbon whiskey enthusiast is having so much diversity in maturation styles. Heat is one of the main things that separates whiskey aging in the United States apart from almost all other whiskey major producing countries in the world – Scotland, Ireland, Japan and Canada. Even countries that have a warm climate won’t get the same effect when maturing because the barrels they use have been used before. Ironically, a majority of them were filled with bourbon in their previous life.

This leads me to the point of what I’m going to be talking about today. The reason that bourbon tastes the way it does is because it was aged in a new oak barrel. But if all bourbon made from the same distillery was matured in the same new oak barrels, then why doesn’t it all taste the same? The reason has to do with where the barrels are stored for all of those years.

If you’re not familiar with how Kentucky Distilleries age their barrels then I’m here to tell you that they all have their own way of doing it. Out of all the distilleries across the Bluegrass State, perhaps none are as unique as the ones at Brown-Forman Distillery and Woodford Reserve Distillery.

Chapter 1: Artificial Heat, Masonry and Bourbon: Barrel maturation the Brown-Forman way

At this point, you’re probably thinking “why do I need to care about the building my bourbon is aged in?” And why did I pick the very consistent heat-cycled warehouses that Brown-Forman distilleries use? After all, Brown-Forman warehouses built after World War II are almost all the same size and use the same construction specifications from campus to campus. This should allow the whiskey to mature in a consistent manner.

Taking it one step further, brands like Old Forester and Woodford Reserve only use one mash bill and one barrel entry proof for their respective bourbons – so it’s not like there are a lot of choices when it comes to variety. But that’s precisely the reason why every little difference matters when you’re trying to decide which product speaks to you the most. This is also why enthusiasts like to obsess over the details and find the differences.

Before we begin, let me make sure we’re all on the same page. I’m going to be talking only about Brown-Forman’s warehouses inside of Kentucky. So if you’re here to find out more about Jack Daniels, you might be disappointed. The following article is only going to cover Old Forester and Woodford Reserve.

The same, but different

Brown-Forman’s style of warehouses are almost entirely made from some sort of masonry. So what? Other distilleries have warehouses that are made from brick or stone. Brown-Forman’s style of warehouses also have steam-heating pipes connected to each one to warm them during the wintertime. So what? Buffalo Trace has that too. Brown Forman’s style of warehouses are temperature regulated to achieve consistent maturation results across their floors. So what? Four Roses, Maker’s Mark and Heaven Hill employ shutters designed to regulate temperatures as well. None of this seems like they are doing anything different. What it boils down to is how they combine each of those specific attributes to make their aging unique. Here’s how:

Heat

For starters, Buffalo Trace uses steam heat pipes (and other methods for their newer warehouses) to achieve a baseline minimal temperature in the winter months. They typically aim for a minimum of 58 degrees so that their barrels don’t go into what’s called “dormancy.” A few degrees under this number means that the barrel and the wood are no longer interacting. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, but Buffalo Trace demands consistency among their products. Doing so means that they must ensure that all of their barrels are taking full advantage of every moment they spend in a warehouse – and not being dormant.

Besides that, without some sort of minimal heat regulation, the lower floors will see their barrels become dormant much sooner than the upper floors.

Old Forester uses what is known as “heat cycling.” This process involves having steam heat pumped into the warehouses throughout the colder months whenever a sensor attached to a barrel alerts a computer that the temperature is too low. Steam heat will usually pump in until the air gets up to around 85 or 90 degrees inside the warehouse. This is far hotter than Buffalo Trace’s warehouses will get during the winter months. At this temperature, the whiskey should see an increase to its temperature to about 75 degrees.

At this temperature range, the distillate is actively being pushed into the wood just like it would in the summer months. Then the whiskey extracts itself from the wood and back through the layer of char (which is basically charcoal) as it cools back down. This process creates a mellow character.

What’s the goal of this? If you look at it through the lens of a maturation expert, it’s so that multiple cycles can occur throughout the winter. This will allow the whiskey to develop a more mature profile over a shorter period of time.

If you want to look at it like a businessman, it’s so that you can move more product at a faster rate that tastes about the same age as your competitors. This allows you to be more competitive than the other distilleries who had to age theirs for longer. In this way, you can bring more whiskey to market in a shorter period of time which should offset the energy costs it took to heat them first place. Additionally, you don’t have to build and maintain as many warehouses to churn out the same amount of product.

There is one drawback of heat-cycling, though. And that’s the evaporation rate can be almost double that of traditional aging. Brown-Forman reps claim that as much as 10% could be lost per year as opposed to 4-5% evaporation losses in a traditional warehouse. Ouch.

Building Construction

As I’ve already hinted to, Brown-Forman warehouses are almost entirely made of masonry (brick, formed concrete or limestone) and steam heated. On the Brown-Forman Distillery campus (formerly called Early Times Distillery), there are now only 7 brick warehouse that are 4 stories tall. Each story is split in half with a mezzanine floor surface, so technically there are 8 “floors” where the workers can access 3 tiers of barrels. The exception was Warehouse O, which was recently demolished. It was a single story, non-heated, metal warehouse with ricks 6 tiers high (similar to Four Roses).

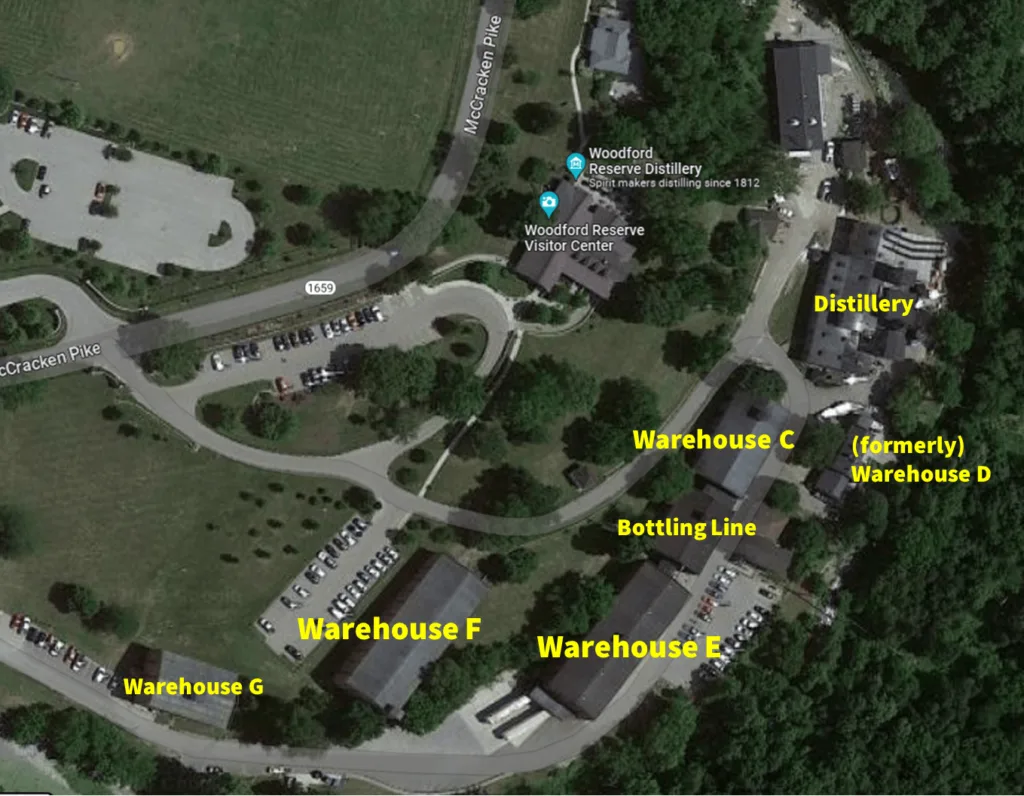

Woodford Reserve has two different styles of warehouses. The original ones (built in the 1800s) are made from limestone and are two stories tall on average. Numbers have not been given as to how many barrels they can hold, but an article on kentucky.com indicates that prior to the new (humungous) warehouses being built, that the original campus could only store 8,000 barrels. These were only stored in Warehouse C.

Four brand new warehouse were constructed by 2015 and were designed from the start to store barrels in a palletized method. The pallets would be stacked 7 high and each warehouse would be able to hold around 55,000 barrels. That puts the total number of barrels being stored in Versailles at just under 230,000 (some media quotes the amount at 260,000). This is very similar to the size and scope of the Brown-Forman Distillery Warehouses in Shively.

While my primary focus will be on the warehouses at Brown-Forman Distillery in Shively, let’s look at Woodford Reserve’s operations first.

Chapter 2: The Warehouses at Woodford Reserve

Woodford Reserve was originally known as the Old Oscar Pepper Distillery in the mid 1800’s before becoming the Labrot & Graham Distillery. It is said that even by 1838, the first warehouse used to store barrels of whiskey was heated by steam heat. I’m not sure if this is entirely correct because the main distillery building itself was completed in 1838. It is my assumption that the storage warehouse and the building that contained the pot still were the same building.

Regardless, steam heating was apparently somewhat common in the early days of whiskey maturation among different distilleries. But steam heating is not as effective if the building is made of wood due to the gaps that naturally occur. So masonry (limestone pieces, specifically) was used in the construction of the original Woodford Reserve buildings. Few windows and doors were installed, which allowed the heat to remain inside for longer at a more even rate. When Brown Forman eventually began the rehabilitation processes to bring the distillery back to life in 1993, they reconditioned the buildings and the steam heating system to be viable again.

If you’ve ever taken the Woodford Reserve Tour, you will probably remember the rickhouse you’re led through shortly before you go into the bottling line building. That’s Warehouse C. I’m not sure if it’s heat cycled or not because the doors seem to remain open pretty much year-round for the tour groups to walk through. But there are four other warehouses that used to store barrels. Warehouse D (see picture) and is now used as a bottling house while Warehouse E is “Shipping and Receiving.” Unfortunately, F and G are vacant at the moment with no plans for them to store barrels in the future.

As I mentioned before, total barrel capacity for an older warehouse like “C” is supposedly only 8,000 total. So once you view the entire campus on a map, you start to realize just how small the older buildings are to the new ones.

Woodford’s popularity was so explosive, that Brown-Forman had four new warehouses built beyond the line of sight due east from the Visitor’s Center. These warehouses are modern in every way from their construction material (concrete walls with a façade that makes them blend in with the limestone rock style of the other buildings) to their fire suppression systems and their climate control systems.

I could not find an answer as to if these warehouses have an alphanumeric identifier and will update this if I ever come across it. Until then, we only have pictures like this to guide us.

Barrel storage: ricked versus palletized

There is one main difference though: the barrels that are aged within do so in a palletized position. That means they spend their life upright on pallets that are stacked on top of each other with a forklift. Most producers that stack palletized barrels only go 6 high (like MGP). Woodford chooses to go 7 high with theirs.

What differences can be expected when barrels age upright on pallets? Typically, the barrels are stacked much more tightly next to each other. That restricts airflow that could allow for the barrels to warm up and cool down in a more even, consistent manner. This will result in barrels aging on the outside of the stacks to age differently from the ones on the inside over time.

A not-so-well kept secret about Woodford Reserve is that their standard bourbon (and rye whiskey) are batched together with barrels distilled from the same mash bills at the Brown-Forman Distillery. This has been done since 2003 and is because the triple pot still distillation technique results in an exceptionally light bodied and floral distillate (similar to Irish Whiskey) due to the high proof they distill it to – around 158 proof (just shy of the maximum that bourbon is allowed to be distilled to). Brown-Forman was concerned that American consumers may not enjoy the flavor or body of that style of bourbon so Old Forester was blended in to give it more of a bourbon character.

Extra-aged Woodford Reserve Products

Woodford Reserve does not typically age their products past 6 years. That’s why products like the 16th release of Woodford Reserves Master’s Collection Very Fine and Rare Bourbon was such a shock. It contained barrels as old as 17 years and many more aged to 11 years. Other than that, only a few Woodford Reserve Master’s Collection products contain whiskey aged outside of the normal range.

It can be assumed that Woodford didn’t allow these barrels to be aged in heat cycled warehouses for that entire length of time. Perhaps they were moved to Warehouse C for a period of time to prevent rapid evaporation losses. Maybe Woodford stopped heat cycling one of the smaller warehouses that stored these barrels. It’s all unknown at this point. Temporary heat-cycling is a concept we’ll see later on when we explore how King of Kentucky was made at the Early Times Distillery.

Chapter 3: The Warehouses at Brown-Forman Distillery

Before I begin, I’d like to point out that the following information is designed to be read side-by-side with this article analyzing the statistics of barrels pulled from Brown-Forman Distillery Warehouses. Please read it after this next section!

Brown-Forman Distillery was known as the Early Times Distillery until relatively recently. In 2018, slightly before Brown-Forman’s decision to sell the Early Times brand to Sazerac, they decided to change the name. As an aside, the more research I’ve done, the more I feel like Brown-Forman had a plan to shed the Early Times brand as far back as 2017. Call it a hunch, but the distillery name change is a little too on-the-nose.

A little-known secret is that the Early Times mash bill continues to be made at the distillery in small amounts for the King of Kentucky line. Nowadays, the distillery primarily churns out only Old Forester whiskies. Some of the rye whiskey that is used in Woodford Reserve Rye Whiskey (known internally as the Old Watermill recipe according to interviews with Chris Morris) is distilled at Brown-Forman Distillery too. This is separate from Old Forester’s rye whiskey which is known internally as “Normandy Rye.” Any whiskies destined for a Woodford Reserve product, however, will eventually be trucked to the Woodford campus to finish aging there.

The Brown-Forman Distillery only has 7 warehouses right now. A quick look at the map might make you think there are only 4. That’s because 3 of the warehouses that share a common wall between them. Here’s a map to show how they look like.

Before we get into what makes each warehouse special, let’s look at some of their shared characteristics.

Windows

Almost every distillery warehouse I’ve ever been in has windows in it. Most of those windows are more like slats that can open and close to let air move throughout. Few have actual windows with the main purpose of letting in sunlight like Brown-Forman’s do. It creates a unique maturation trait that Jackie Zykan often talked about on podcasts. You see, a lot of the windows expose the barrels that are nearby to direct sunlight. The barrels, in turn, develop a deep tan color (almost to the point of looking orange) as they age. This extra sunlight exposure undoubtedly raises the temperature inside of the barrel much more than the other barrels on that floor.

Surely this exposure creates a bourbon that tastes different from the rest. Sadly, Old Forester does not comment on barrel location or rick location when they do the single barrel program.

I have a theory about where those barrels end up – the Old Forester Stateman line of bourbon. Years ago, Jackie said on the Bourbon Pursuit podcast that Statesman wasn’t just a bourbon that was made up of random barrels – she said that since The Kingsman movie franchise (which the bourbon came from) was considered a “hot movie” in terms of action and overall feel. In turn, the barrels chosen to go into the Statesman line would be collected “from the hottest parts of the warehouses.” She said that there were known locations that would be hotter than others and that’s where they got the barrels from. These barrels next to the windows sure seem like they’re just what she was talking about. Either that or directly next to the heating outlets in the walls.

The Mezzanine Floors

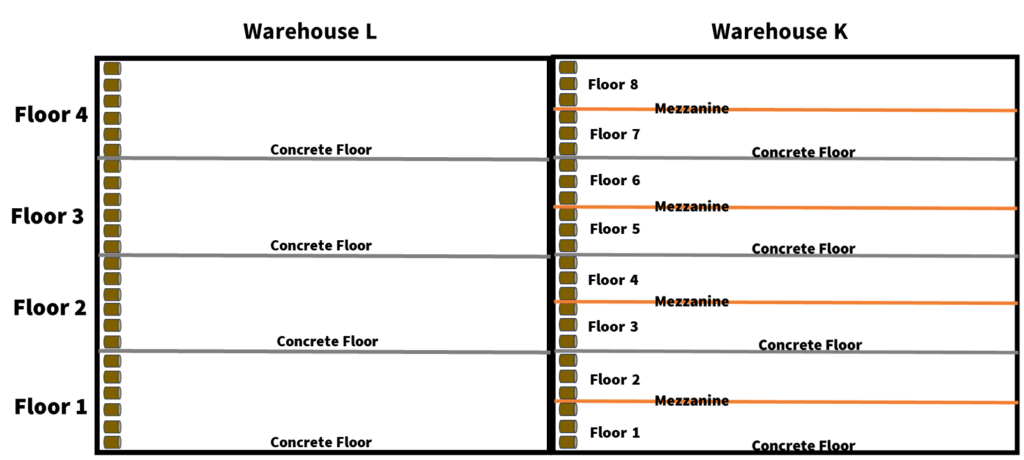

One similarity that Brown-Forman Distillery warehouses share with other Kentucky distilleries is that their ricks are 6 barrels tall. But Brown-Forman does something unique that I’m not sure any other distilleries have done. They have built a mezzanine floor halfway up the rick. This effectively doubles the number of floors in a warehouse. So even though Brown-Forman Distillery warehouses have 4 true floors, they technically have 8 (well, most of them do, more on that later).

The mezzanine is supported by a series of sturdy braces that allows barrels from ricks 4, 5 and 6 to be accessed much easier. There are even gaps throughout so that you can see the barrels in the first three ricks. I believe this is to allow better airflow overall without increasing the risk of a worker falling through them. Look at these pictures for an idea how it looks from the inside.

How Heat Cycling Is Regulated

Most people already know that Brown-Forman heat-cycles their warehouses. But what does that mean exactly? Is somebody flipping a switch every Friday night to turn on the heat? No. Instead, temperature probes are inserted into barrels that are located in the center of the warehouses on floors 1, 3, 5 and 7. They collectively gather data on the liquid’s temperature. When the liquid gets below 65 degrees, steam heat is pumped into the warehouse to raise the temperature. According to Jackie Zykan, the heat is not stopped until the liquid reaches 75 degrees – then the heat is shut off to that warehouse.

What this means is that heat-cycling is not dependent on a date on the calendar – it’s based on the weather outside and how it affects the temperature inside of the warehouses. I wanted to clarify this because many people quote numbers like “the warehouses are heat-cycled 12 times each winter” which could be true for one year, but wouldn’t apply to all of the years.

Now let’s direct our attention to the warehouses. I’m going to go in order by when they were built, from earliest to latest.

Warehouse A

Warehouse A is the only warehouse of Brown-Forman’s that is not on the Brown-Forman Distillery Campus. It is located on the main Brown-Forman Corporation campus. But if you’ve drove though Shively, I guarantee you’ll know where it is – it’s the building with the giant bottle of Old Forester on the top (Surprise! There’s a water tower inside of it).

I could not get an accurate date of when the warehouse was built but suffice to say that it was probably before Prohibition was enacted in 1920.

The entire warehouse had been physically sealed up by the Louisville Fire Department years before Brown-Forman decided to transform it into office spaces on the inside. Work began sometime around 2015 and was a huge undertaking since the warehouse was around 100 years old at that point. The floors were removed in favor of a large open space while offices ran around the edges. Additionally, electricity and fire suppression had to be installed to bring the building up to code since people would work in it now.

There is even an underground tunnel (called the Bourbon Street Tunnel) that was built in 1995 to run underneath the Dixie Highway connecting the main campus with the Brown Forman office complex across the street.

Warehouse O

Warehouse O was the oddball of the Brown-Forman campus up until its demolition in 2022. It was constructed on the south end of the distillery building sometime after Prohibition was ended in 1933. The other warehouses were constructed north of the distillery. Warehouse O was the only aging warehouse that was not made of brick or had steam heat plumbed to it. It was metal clad and only 1 story tall. Inside, it had 6 tiers of ricks.

The lack of a heat-cycling system meant that barrels stored inside would go dormant during the winter months. The upside was that evaporation losses were lower over the same period of time compared to the barrels stored in the brick warehouses.

Since Warehouse O was not heat-cycled, that meant that the average cost to mature a barrel inside was lower than the heat cycled ones. Why does cost matter? Because it gives us a clue as to what products were originally stored in it. The most obvious were Early Times distillate – specifically the used barrels that held the “whiskey” component used for Early Times American Whiskey. It can also be assumed that most Early Times bourbon was also stored in this warehouse. As the years went on, Early Times sales decreased to the point where they weren’t selling that much of their whiskey anymore. A lot of the barrels of whiskey (not bourbon) grew much older than the 3 years they were meant to mature.

Along those same lines, there was a post by Michael Veach on the forum straightbourbon.com back in May, 2006 where he comments that Early Times had barrels as old as 8 years were being used because sales of that kind of whiskey was so slow. It is unclear if he meant bourbon or whiskey, but there were other rumors that the source of all of the 18-year-old American Whiskey that Barrell Craft Spirits bought up in 2019 was sourced from Early Times as well.

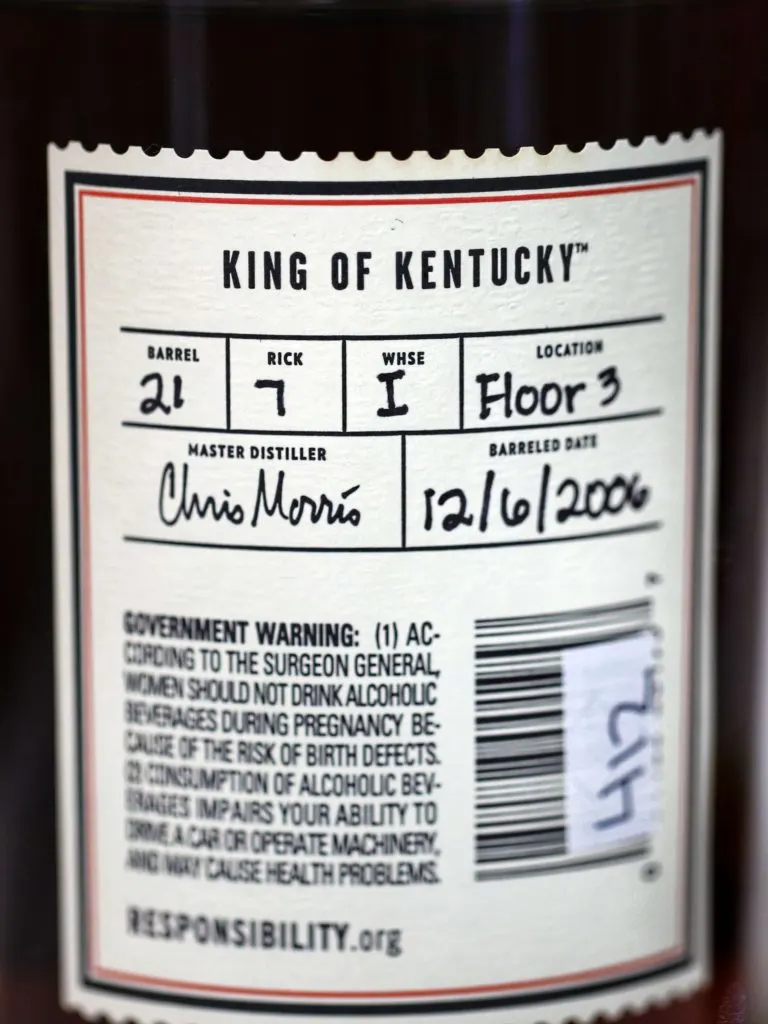

One of the most impressive bottles to come out of Warehouse O was King of Kentucky. For those of you who have had King of Kentucky, you may be questioning that statement since the rear label usually states another warehouse on it. The truth is that all King of Kentucky barrels started as Early Times bourbon (79/11/10) and were probably aged in one of the 7 heat cycled warehouses for up to 7 years. At that point, they moved the barrels out of the heat-cycled warehouses and into Warehouse O for an extra 7 or more years. This was done to limit the amount of evaporation in the barrels but it also explains why many KoK barrels typically have bottle yields between 50 to 70. But Warehouse O hasn’t had any barrels in it since at least 2021, so where are the King of Kentucky barrels aged at now? I’ll cover that soon.

As a final note, I want to point out that there were a handful of Old Forester Single Barrels that came from Warehouse O from 2018-2019. These are the older 90 proof versions. One of the key characteristics about each one is that they all say “Floor 1” on them. When Old Forester discontinued the 90 proof single barrels in favor of the 100 proof and Barrel Strength varieties, there was exactly 1 barrel that was ever bottled up for sale in Barrel Strength form; a Master Taster Select (MTS): The Last of O House.

Starting around 2020, the barrels in Warehouse O began to be vacated. Ricks were removed and much of the space was used as storage. By 2021, there were no more barrels left inside. The warehouse was finally torn down in late 2022. Jackie Zykan lamented in a podcast she was on in late 2021 that she wanted to see each warehouse be bottled as a 117 series label. Did anyone save any of the Warehouse O barrels to make this happen?

Warehouse B

Warehouse B stands by itself as the northern-most warehouse on the Brown-Forman Distillery campus. It was the first brick warehouse built on this campus. I couldn’t track down the definitive date that it was constructed, but my estimate is 1949.

Warehouse B is the only warehouse of the remaining 7 that does not age barrels on the first story. I’m unsure if this is the way it’s always been too since a barrel dump-and-filling system resides there. To expand on this a little bit more, I looked into why this bottle release article (see below) from May, 2023 claims that barrels were stored on the bottom floor of Warehouse B and why they were not heat-cycled.

This article seems to be wrong on 2 levels. The first is that Floor 1 of Warehouse B is not able to store barrels. Maybe some barrels got moved into this space from somewhere else and were forgotten about for a period of time. Secondly, Warehouse B is a heat-cycled warehouse, so if it came from B, it was heat cycled. Regardless, this whole article stinks of misinformation. I hope nobody took it seriously.

Statistically, single barrels from Warehouse B are very rare. Let’s break down the reasons why. The first is because the barrels pulled from there only come from Floors 3 through 8. That means that right off the bat, Warehouse B can only hold 75% of the barrels the other warehouses can. The second reason is that around 2019, no new barrels were put into the warehouse. Why? Because it was being massively renovated whereby the mezzanine layers were removed between the floors and new metal ricks are being installed. Once the renovations are complete, Warehouse B should start being filled with (new) barrels. That means that we probably won’t see any Single Barrel picks coming from Warehouse B for at least 4 more years.

Notable Warehouse B Releases

Half of the barrels selected for the 2009 Birthday Bourbon release were sourced from the 5th Floor

Warehouse G and H

Originally I thought that all of the Brown-Forman warehouses were built at the same time. Later I found out that wasn’t true. Warehouse G and H were completed after Warehouse B – sometime around 1951-52. Internally, they have the same layout as Warehouse B, but Brown-Forman planners decided to save real-estate by joining the two warehouses together with a common wall.

The biggest news of this entire article may be this next part; sometime around 2018 or 2019, Brown-Forman decided to stop heat cycling these 2 warehouses. I don’t know the specifics of how they did this but the steam heat from the central boiler has stopped flowing into its floors. As a result, the barrels inside typically become dormant early in the winter as temperatures plummet under 50 degrees. When spring comes around, it takes around 2 months longer for the temperatures inside to catch back up to the other warehouses.

This is interesting because Warehouse G and H now act like Warehouse O – only with the ability to hold more barrels than O did (they each hold about 50,000 barrels). The coincidence of when Warehouse O was starting to be emptied (~2018) and when Warehouse’s G and H stopped being heat cycled (also around 2018) make it seem like this was actively planned out.

Let’s expand on this for a minute. Why would Brown-Forman decide to stop heat-cycling these two warehouses (around 100,000 barrels)? I have a couple theories. The first is that they are experimenting with how their barrels will mature over the same period of time compared to the heat-cycled warehouses. If they find out the profiles of the barrels end up being the same while only needing an extra year or two to age, then why spend the money to heat the other warehouses?

The second reason is that slower maturation times will result in higher age statements. No longer will Old Forester products have to hide the true age of their products, they can now play on the same ballfield as their competitors like Heaven Hill, Jim Beam or Wild Turkey. In fact, we may be seeing the fruits of this experiment in two recent/recently announced labels – The 117 Series Bottled-in-Bond (which is 9 years old) and the upcoming Old Forester 1924 Whiskey Row Series (which will be 10 years old). It is highly doubtful that either spent their entire life in the heat-cycled warehouses.

Up until now, the only way to get anything that was age stated was to buy an Old Forester Birthday Bourbon (usually between 10 and 12 years old), Old Forester President’s Choice (age statements vary from 6 to 10 years old) or a bottle of King of Kentucky (14 to 18 years old). Brown-Forman never reveals the age statement on their regular line of products (which are roughly 4.5 years old) because they know that uneducated consumers might stop buying their products if they think it’s inferior to other brands. After all, it takes a while for even regular enthusiasts to learn that heat-cycling matures bourbon faster than traditional rickhouses.

But the real reason may just center around money. If Brown-Forman finds that the bourbon that comes from these warehouses end up being similar to the kind that come from the heat-cycled ones, they may decide not heat-cycle any of them anymore. With fuel and electricity prices rising rapidly these days, the cost to heat-cycle these warehouses is probably encroaching on BF’s profit margins.

So what does the lack of heat-cycling mean for Warehouse G and H single barrel picks? For starters, the average barrel strength proof of barrels that come from them are slightly lower than their heated counterparts. From some quick averages I ran in the follow up article this one, I find that barrels from Warehouse G and H run about 1.5 proof points lower on their bottom floors and as much as 3 proof points lower on their high floors. These are not-insignificant differences.

Also, I’ve heard from a few sources that selected Warehouse G barrels in the 2021 timeframe that they were told their barrels were 6 years old. That flies in the face of the other heat-cycled warehouse picks that were typically 4.5 years old max. Did Old Forester purposely allow the barrels to age an extra 1.5 years to offset potential issues in maturation? I think the answer is yes.

All of this is to say that your Warehouse G and H picks may not taste the same as the other warehouses because the aging process is different. Let the games begin on comparison reviews between heat cycled and non-heat cycled warehouses!

Notable Warehouse G Releases

Half of the barrels selected for the 2014 Birthday Bourbon release were sourced from the middle floors

93 barrels selected for the 2017 Birthday Bourbon release were sourced from the 4th Floor

119 barrels selected for the 2021 Birthday Bourbon release were sourced from the warehouse

Notable Warehouse H Releases

Barrels selected for the 2005 Birthday Bourbon release were sourced from the 7th Floor

Barrels selected for the 2006 Birthday Bourbon release were sourced from the 7th Floor

Barrels selected for the 2008 Birthday Bourbon release were sourced from the 6th Floor

Half of the barrels selected for the 2011 Birthday Bourbon release were sourced from the 1st Floor

Barrels selected for the 2012 Birthday Bourbon release were sourced from the 4th Floor

2022 – All King of Kentucky Single Barrels were sourced from Warehouse H (possibly all from the 7th Floor)

2023 – The 117 Series releases “Warehouse H” – made entirely from barrels matured inside the warehouse

Warehouse I and J

Constructed sometime between 1952 and 1953, these two warehouses also share a common wall. But unlike G and H, they are heat cycled. In terms of unique attributes about I or J, nothing much stands out. They both still hold the same amount of barrels (50k each) and have 8 floors (4 stories tall).

When I crunched the numbers on average proofs between the warehouses, I found that Warehouse I stood out from the rest as having highest average barrel proof overall as well as two of the top 3 highest proofed barrels to be released in the single barrel program – a 136.5 proof pick from THE FIRST FLOOR (ABC Fine Wine & Spirits) and a 136.0 proof pick by Depot Liquors that was found on the 8th floor. Warehouse J had the second highest average barrel proof overall. What I think this suggests is that the heat that enters these warehouses is somehow hotter than the heat that enters B, K or L.

If you ever find yourself walking around these warehouses (which is very tough to do), you’ll find the windows open for Warehouse I, J, K and L much more than Warehouse G and H. A friend of mine who works for OSHA said it’s actually because as the barrels age in hotter temperatures, they give off more ethanol fumes. Why this matters is that OSHA has regulations on the levels of ethanol exposure that can be accumulated every 8 hours. Therefore, the warehouses that are heat cycled must have their air exchanged at a faster rate than the non-heat-cycled warehouses so that the vapors don’t accumulate to unsafe levels. This is to reduce the potential for fires, explosions and occupational health.

One interesting thing to note is that on the east-facing side of all Brown-Forman warehouses, there is an external, exposed metal elevator device that is designed to move barrels to and from the floors that the workers roll them to. This is how each floor loads and offloads their barrels into the trucks that move them around the campus. It must be very tedious because when I observed it, I only saw one barrel able to be loaded at a time.

Notable Warehouse I Releases

Half of the barrels selected for the 2011 Birthday Bourbon release were sourced from the 6th Floor

Barrels selected for the 2013 Birthday Bourbon release were sourced from the 7th Floor

Half of the barrels selected for the 2014 Birthday Bourbon release were sourced from the middle floors

27 barrels selected for the 2018 Birthday Bourbon release were sourced from the 3rd Floor

Barrels selected for the 2019 Birthday Bourbon release were sourced from the 2nd Floor

Barrels selected for the 2023 Birthday Bourbon release were sourced from the 5th Floor

2021 – All King of Kentucky Single Barrels were sourced from Warehouse I (possibly all from the 3rd Floor)

The highest-proofed Barrel Strength Bottle came from this warehouse clocking in at 136.5 proof

Notable Warehouse J Releases

Half of the barrels selected for the 2009 Birthday Bourbon release were sourced from the 8th Floor

93 barrels selected for the 2018 Birthday Bourbon release were sourced from the 3rd Floor

Warehouse K and L

Warehouse K is arguably the most well-known Brown-Forman warehouse of all. Even before Old Forester launched their single barrel program, it seemed like there was some buzz around how the best barrels came from Warehouse K. This originated from a podcast that Jackie Zykan did sometime around 2018 where she expressed her love of barrels that were pulled from there. Enthusiasts who listened to it became enamored with it and that made it an overnight sensation.

In reality, Jackie never really meant to single out a specific warehouse as her favorite and went on to express her love of each warehouse. In a podcast she was on in late 2021, she became excited at the prospect of having each warehouse highlighted in the Old Forester The 117 Series line. So far, we have only had examples from Warehouse K and H. Will we see the others in the future?

Back before Brown-Forman got so serious about such things, there used to be the occasional tour where outsiders would get shown the distillery and one warehouse. That was Warehouse L. Warehouse L was the last warehouse to be constructed (sometime around 1953) and shares a common wall with Warehouse K. The one key difference between the two is that Warehouse L has no mezzanine between the floors. The lack of a mezzanine makes the space inside much more open and bright than the tight quarters of their standard floor layout. It also means that Warehouse L only has 4 floors instead of 8.

I could not find out a reason why Warehouse L was the only warehouse to be constructed without a mezzanine. I believe it was to cut costs to the final construction bill of the warehouse. But since they were all built so close together in terms of time, why didn’t others delete this feature too?

After seeing that Warehouse B’s mezzanine is also being gutted, does this mean that Brown-Forman is going to push for them to be removed in every warehouse? Stay tuned.

Notable Warehouse K Releases

Barrels selected for the 2010 Birthday Bourbon release were sourced from the 5th Floor

93 barrels selected for the 2016 Birthday Bourbon release were sourced from the 3rd Floor

27 barrels selected for the 2017 Birthday Bourbon release were sourced from the 3rd Floor

2018-2020 – All King of Kentucky Single Barrels were sourced from Warehouse K (possibly all from the Floors 5 and 8)

2021 – The 117 Series releases “Warehouse K” – made entirely from barrels matured inside the warehouse

Notable Warehouse L Releases

Barrels selected for the 2004 Birthday Bourbon release were sourced from this warehouse

Whiskey Row Old Forester Distillery DSP-KY-117 Warehouse

Technically, this is a distillery, visitors center, cooperage, bottling line and warehouse all in one location. I’d be remiss if I didn’t include it in my list of warehouses because it is the only “warehouse” on the list that the public can take tours of. Personally, I think they missed a golden opportunity to showcase how their regular warehouses work. Why not seal off the warehouse portion and heat treat it as well?

Instead, we get an almost antiseptically clean building that’s an architect’s dream come true. Perhaps the best part is that you can actually reach out and touch an aging barrel. I’ll admit, it’s an impressive sight to behold, but an accurate portrayal of how Brown-Forman barrels are actually aged it ain’t.

Instead of being heat-cycled, the barrels are stored in an environment that’s only “temperature controlled.” What they must mean by that is the temperature is controlled enough to keep visitors comfortable while they take the tour. I don’t imagine the inside ever gets over 80 degrees in the summer. As such, the barrels should have a relatively low evaporation rate in here.

The barrels that I witnessed on my tour were all branded with the DSP number of the distillery. This would indicate that they were made on “Big Penny,” the 24” diameter column still that greets visitors walking into the gift shop. I would assume that the mash bill used to fill these barrels is the same as what is used to make Old Forester at the Brown-Forman Distillery (DSP-KY-354), but those column stills are much larger. That means that the whiskey should actually taste slightly different. I wouldn’t put it past the minds at Old Forester to eventually have a 117 Series release made entirely from the barrels distilled at DSP-KY-117. Makes sense, right?

Future Old Forester Warehouses

Brown-Forman has plans to vastly increase their presence in the contract-distilled marketplace. Currently, they’re putting their name out there and gauging interest who would want their whiskey distilled and barreled by them. From some sources I’ve heard from, the prices are among the highest in the industry compared to the programs ran by Bardstown Bourbon Company or MGP. As of early 2023, I haven’t been aware of anyone actually signing up to have barrels laid down by them yet.

But when it eventually happens, Brown Forman is going to need more space to store these barrels (assuming the customers will want them aged as well). With the limited space available at the Brown-Forman Distillery, my assumption is that a new warehouse (or more) will be built in the old Warehouse O footprint. Otherwise, there isn’t much room to expand in any direction at the Brown-Forman Distillery. I wonder if they’ll decide to build a warehouse that will be designed to hold barrels in a palletized configuration (like Woodford Reserve).

Brown-Forman might be able to buy some land north of their offices on their main campus, but time will tell if they are feeling the squeeze on barrel storage locations. There’s also the idea that they could build warehouses in cheaper locations like Indiana just like they did from 1962 to 1984. But that might be an extreme strategy in this day and age.

Extra-aged Old Forester and King of Kentucky Products

The best-known Brown-Forman product that wears a high age statement is Old Forester Birthday Bourbon. Throughout the 20+ years it has been bottled and sold, its age statement has fluctuated between 10 and 12 years old. These aren’t a product of luck, either. Barrels are identified early on in the maturation process and then carefully monitored to ensure that evaporation doesn’t get to them. And while nobody from Old Forester has ever admitted this, I personally think they moved them to Warehouse O in the past or even Warehouse G/H in the present in order to prevent runaway evaporation.

This is what they did to King of Kentucky bourbon, after all. Barrels were identified early on and they were pulled from their original warehouse after around 7 years to finish aging in Warehouse O. Now that it no longer exists, I believe that these barrels are being put into Warehouse G or H. It would be nearly impossible to get the kinds of yields they get after 14-18 years in a heat cycled warehouse.

The same year that King of Kentucky came out, we started to see Old Forester President’s Choice bottles brought back to the market. Granted, King of Kentucky and President’s Choice bottles comprise of around 30 barrels per year, but that still indicates the need to have lots of warehouse space available that isn’t soaking the barrels with heat all year round. Now that they seem to have a process down and are releasing much more eye-catching age statements, will any of that trickle down into the more mundane releases?

To speculate even further, I’m assuming that Brown-Forman’s experiment with turning the heat off to Warehouse’s G and H is going to usher in a new age of highly (relative to the rest of their products) aged products that aren’t priced through the roof. In 2023, we’ve already seen the release of a 9 year old The 117 Series Bottled in Bond bottle. We’re also slated to see a new addition to the Whiskey Row series (1924) that sees an incredible 10 year age statement. These could be the bellwether towards a future where there are more age-stated products from Brown-Forman. I can’t wait!

Epilogue

It’s been a fascinating process tracking down all the things that make Brown-Forman’s warehouses unique. I was initially expecting to find nothing much of interest but quickly learned that each warehouse had a unique story that, once understood, started to make the products Brown-Forman released come into focus. These are the things that enthusiasts are hungry to learn about. I know there are probably many high-ranking executives at Brown-Forman that think that enthusiasts don’t care about this kind of stuff, but we do.

The more I learned, the more questions arose. I still don’t have answers for them, but I’m going to put them here in an effort to show that this article is a work-in-progress. If I find out answers in the future, I’ll come back and edit it. They are:

- I pored over hundreds of pictures of unique single barrels and found gaps in the warehouses and floors that haven’t been used. Warehouse H – Floor 1, Warehouse J – Floors 1, 5 and 7 and Warehouse L – Floor 2 have no single barrels that came from them. Are these floors used for something unique?

- Warehouse I has the highest overall average proof for the barrels that are pulled from it (I’m not counting Warehouse B since there are only 3 floors that barrel strength picks were harvested from). In fact, Warehouse I had the highest proofed single barrel that I observed as well (a 136.5 proof picked by ABC Fine Wine & Spirits). What makes this warehouse so susceptible to producing such high-proofed barrels?

- Every floor should contain a variety of mash bills (Old Forester and Woodford Rye Whiskey recipes, Old Forester Bourbon recipe and Early Times bourbon recipe), but why is it that only rye whiskey comes from Warehouse K – Floor 7?

- Steam Heat as a means to heat-cycle the warehouses would be incredibly inefficient. The most efficient means to heat a warehouse would be radiant-heat flooring, but retrofitting this would be cost-prohibitive in all but Woodford’s newest warehouses. Is there another way that Brown Forman heats their warehouses? Do they use a heating coil attached to an air vent instead? Have they considered switching technologies to cut costs?

- If Brown-Forman is going to make a shift towards non-heat cycled warehouses, will this dilute their ultra-premium brands like Birthday Bourbon, President’s Choice and King of Kentucky? Or will they be pumping up the volume on them even more?

- Don’t forget to look over at my article analyzing the statistics of barrels pulled from Brown-Forman Distillery Warehouses next! It’s going to go into detail on the proofs and profiles of the single barrels that come out of the remaining 7 warehouses! Cheers!

Featured Products

- Neat Traveler

- View Larger

- Description:The Aged & Ore Neat Traveler is a complete travel kit for spirits. We combined our widely praised Neat Glass with one of our 3oz Flight Bottles and housed them together in a custom EVA travel case. Perfect for a night away with your favorite pour. The tie

- Bottle Flight

- View Larger

- Description:The Aged & Ore Bottle Flight is a premium set of 4 custom silicone wrapped glass bottles designed to transport and share samples of your favorite spirits. The flight bottles come in a custom EVA travel case that fits perfectly in any small bag. An Aged &

- Travel Bundle

- View Larger

- Description:This Bundle combines two of our crowd favorite products, creating the ultimate travel bundle to bring along your favorite spirits and glassware. Bundle Includes: Neat Traveler (Gray) Bottle Flight (Gray) Note: This bundle is only available in gray and col

*Bourbon Culture is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission.